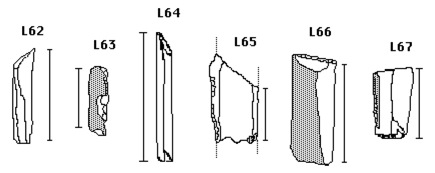

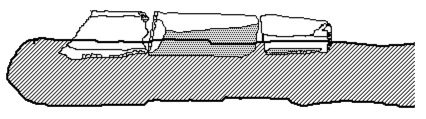

There were also indications that some of these tools were hafted.

It was suggested that there 'cutting soft' tools represented a concentration on the exploitation of vegetable resources. The reeds of the nearby swamp were not the material involved because reeds are silica rich and produce a significant polish quite quickly and this was not the case with these 'cutting soft' tools.

It is particularly difficult to identify the precise worked material when the material falls into the 'soft' category. This is because soft materials produce less stress and abrasion on the tools edge and so produce less use wear, making precise identifications extremely difficult, especially if these tools have not been used for long periods of time (see Bamforth et al. 1990). One way of obtaining greater precision is to carry out post analysis replication. Replicas were made of the tools and used on a variety of soft materials to see if the use wear produced by a particular soft material, (such as meat or vegetable material) can be matched against the use wear on the archaeological tools. Such a programme of experimental replication was carried out in the based on the environmental resources that would have been available at the site (Hardy 1993).

There was no direct evidence, in the form of plant remains, of the presence of tubers or root vegetables on the site (pers. comm. Rob Scaife), but such things as wild carrots and parsnips would have been available and probably utilised by the inhabitants of the site.

The processing of such tuberous plants could have left the kind of use wear traces that is found on these 'cutting soft' tools.”

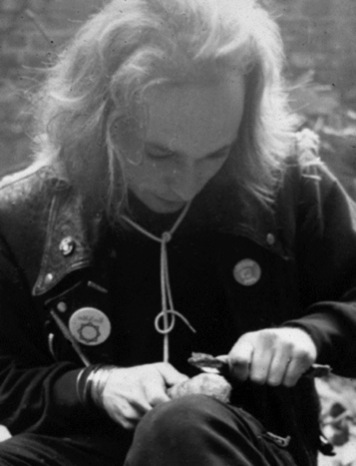

Replicas of the tools from Thatcham were made and used on a variety of materials to see which material produced similar use-wear to that found on the archaeological tools.

Thatcham replicas being used on wood and on parsnips

It was found that tools used on vegetable materials, such as parsnips and carrots, produced use-wear that matched that on the tools from Thatcham.

The emphasis on food gathering supports the idea of Mesolithic subsistence as being primarily a gathering strategy rather than hunting, "... a significant and possibly, in certain cases, a major proportion of flakes, blades, bladelets and microliths may have been associated with vegetal and other food-gathering and processing..." (Clarke 1978, 8). This statement by Clarke would appear to be substantiated by the evidence from the use wear analysis of the stone tools from Thatcham. Use wear analysis can be used to estimate the relative importance of gathering as opposed to hunting, even when there are no, or few, surviving plant remains as is the case with Thatcham. A major difference in the evidence from the stone tools is that it is directly related to the activities of humans. The presence of pollen or plant remains on a site, or from the site catchment area, demonstrates that these plants were available but not that they were definitely exploited. The reconstruction of subsistence strategies from the environmental evidence alone ignores this important point that the presence of a food resource does not necessarily mean that it was actually eaten. To quote Clarke again "...the ecological paradigm has been an important factor in redressing the biased conclusions that emerged from earlier studies restricted to artifact data. However, there has been a disconcerting tendency for essays in this new field to repeat the worst sins of the artifact typologist in a new dimension, merely substituting the differential minutiae of bone and seed measurements and statistics for those of typology and substituting doubtful generalizations based on eccentric faunal and floral samples" (Clarke 1978, 17).

Use wear analysis can gives direct evidence, rather than the assumptions based on environmental evidence, of the importance of vegetable resources in the Mesolithic. The evidence of the prerequisite technology for the processing of vegetable resources (such as composite knives) gives a scenario of a more gradual rather than abrupt transition from a predominantly hunting economy in the mesolithic to agriculture in the Neolithic.